by Charles Whitaker

Forerunner,

"Prophecy Watch,"

August 29, 2005

"Children are our most valuable natural resource." —Herbert Hoover

The previous article focused on the realities of the so-called new demographics, the three-decade-old trend toward measurably reduced fertility rates. The phenomenon appears to be waxing in both depth and breadth—in the magnitude of sub-replacement fertility rates as well as in the spread of these low rates around the globe. Part One also briefly reviewed God's perspective of human reproduction, and the action He will take in the Millennium to reverse current trend lines.

This second part will spotlight a number of moral, social, and technological causes behind the new demographics. It will also look at some short- and long-term consequences of falling fertility among humans. While the present situation does not appear to be immediately dangerous, it nonetheless portends a crisis of major proportions. The implications of depopulation through failure to reproduce sufficiently are frightful.

Causes

Here are the causes generally cited for falling fertility rates:

» Urbanization in an Industrial Environment. The cause classically cited for falling fertility rates pertains to the differing economic realities in rural and urban areas. The coming of the Machine Age witnessed a nearly en masse migration of rural workers to growing urban centers where they could find jobs in manufacturing plants and ancillary service endeavors.

This migration to urban areas has historically resulted in a decrease in family size. Extractive economic activity—farming, mining, ranching, fishing, lumbering—is conducive to large families. Farming, for example, provides couples with short-term financial incentives to building large families. Even quite young children can help with reaping and sowing. For this reason, couples who earn their livelihood extracting raw materials from the earth often have large families.

City dwellers, crammed as they are into small quarters and engaged in heavy industry, lack these incentives. A young city kid cannot do much to increase family revenue. It is hard for a young child to get a job at the local steel mill or locomotive factory. In such an environment, children are more of an economic liability than an asset. Yet, youngsters remain expensive to raise: In America today, a healthy child costs his parents about $200,000 from birth to age 18, not counting college.1 The combination of high, upfront costs and low, near-term payback works together as disincentives for urban couples to invest in large families.2

» Divorce and Casual Liaisons. From 1975 to 1998, 50% of all marriages ended in divorce.3 Divorce lowers fertility in two ways. First, and most obviously, divorce by definition shortens the life of marriages, ending many in the early years when couples would normally have children. Second, more men are deferring or even foregoing marriage because they fear the specter of a messy, costly divorce, where child-support payments will hang over them for years. This is especially true in areas with easy (that is, so-called "no fault") divorce laws on the books. (In fact, "no fault" divorce is thought to be a factor in lowered marriage rates.)

Increasingly, couples are preferring out-of-wedlock cohabitation, where relationships can be brought to an end with no questions asked and, supposedly, no hard feelings. Falling divorce rates do not reflect a turn to moral responsibility by couples, but rather the popularity of "living with" an unmarried partner.4 Pregnancies resulting from such casual relationships are more likely to end in abortion than those coming from relationships in wedlock. Fertility rates fall in these types of casual arrangements.

» Materialism. Say what one might about capitalism, as an economic system, it efficiently (if not maximally) organizes goods, services, and people for production. Hence, modern, Western, capitalistic societies have usually evolved into consumerist societies, driven by commercialism and advertising. Their peoples become enamored by the goods and services industrial societies can produce for them—the cars, boats, homes, vacations, and iPods that become part and parcel of people's definition of the so-called good life.

Like hungry little boys in a candy store, today's Westernized men, women, and children see so much and reach for it all. This invisible and nebulous thing they call "the good life" costs; debt is high, and debt service cuts deeply into spendable income. Couples find that they cannot rear large families and have "the good life" at the same time. Captured by materialistic drives, many opt to have few, or no, children. They do not want to share their "good lives" with children.

» Government Policy. Responding to old socialist myths about overpopulation, many governments have implemented policies that are not conducive to large families. China's one-child-per-family rule is an extreme example. Closer to home, America's tax structure does not adequately relieve the financial burden children create. Tax breaks for dependents are not nearly sufficient to induce parents to create large families. In the 1950s, during the post-war Baby Boom, couples gave up about 17.5% of their income in federal taxes. They could afford to have children. Today, the average federal tax rate is a full 20 points higher, 37.5%.5

» Radical Feminism. During World War II, women entered the workplace in droves. They have not come home yet! The tension between workplace and home, between family and career, has amplified every decade. An almost exact correlation exists between the level of a woman's education and her fertility.6 The more women pursue higher education, the more they compete with men in the marketplace for high-paying jobs, and the more likely they are to defer marriage or childbearing. Many upwardly mobile women forego childbirth until it is too late.7

» Contraception. Another important reason is a technological one: easily available and reliable contraception. Worldwide, about 62% of couples practice some type of artificial contraception.8 Within or without marriage, motherhood has become a choice. The data clearly show that choice translates into less frequency.9 Contraception has become a principal enabler of "planned parenthood," and hence a major contributor to falling fertility. It permits couples as never before to pursue human nature's drive for the things of this world. Couples use it to ensure small families so they can enjoy the materialistic lifestyle they call "the good life."

» Abortion. Finally, legalized, relatively safe, and readily available abortion has contributed to falling fertility rates. Upwards to 46 million abortions take place worldwide every year.10 In much of the world, if a woman becomes pregnant, there are few (if any) legal sanctions, little medical risk, and waning social stigma to murdering the child.

Some of these causes—urbanization and high taxes—have their roots in our culture. Others, such as contraception, are rooted in technology. Still others, such as abortion and materialism, reflect a deep malaise in the morals of millions of people around the Western (and Westernizing) world. All of these reasons interplay to pervert peoples' priorities, diverting them from desiring children to spurning reproduction.

Ironically, this slow suicide by sub-replacement reproduction is so unnatural, seemingly so counterproductive, that few folk a century ago would have dreamed it could happen. It did.

Consequences

Genesis 1:27-28 records God's command to an—at the time—unnamed man and woman. He commands this first couple to multiply. Couples today disobey that command, for whatever reason, at their own risk. What are the consequences of failure to multiply?

"Growing population," one economist claims, "has driven the economy [and] sustained the welfare state."11 Modern economies (and perhaps all economies) are predicated on population expansion. They require market growth to permit the sales of more cars, more boats, and more vacation packages. Sub-replacement fertility rates by definition make market growth impossible and bring into question the viability of Western civilization's economic models. Put differently, in a world of falling human fertility, would you invest in a company that made diapers or toys? For that matter, in a world of declining populations, where each generation the number of potential buyers shrinks with compounding velocities, who would invest in anything?

Whenever economists build an economic model that assumes a declining human population, consumer markets inevitably shrink, while employment and production fall. As GDP falls in these models, capital and equity markets decline in lock step. This is not a pretty picture. For the average person, it translates into fewer and lower-paying jobs, higher prices, lower property values, and erratic capital markets.12

The world has witnessed a foretaste of these ills, at least in microcosm, in Japan's "Great Depression." Starting in the early 1990s, it continues today in spite of some occasional sunlight in the East. Analysts have blamed this extended crisis on misplaced debt alignments, poor performing loans, inadequate banking structure, and unresponsive bureaucracies. Essentially, these analyses address symptoms, not root causes.

Some commentators, however, are gaining a grasp of the true cause of the problem. One, for example, refers to Japan's protracted, perhaps neverending, "aging depression."13 More Pollyanna analysts disavow such doom-and-gloom forebodings.14 Undeniably, though, Japan's situation today is a leading example, perhaps a prototype, of what happens whenever a people fail to multiply in sufficient numbers.

Color the World Gray

At its crux, the problem is one of color: gray. The Japanese are living longer but having fewer children. Increased life expectancies and decreased fertility team up to increase the age of her population. Demographers report age by looking at the mean (or average) age and the median age of a population. (Median age is the age that divides a population into two numerically equal groups; that is, half the people are younger than this age and half are older.)

Japan's population is aging fast for two reasons. First, modern medicine extends life. In 1950, the combined life expectancy of Japanese citizens was 63.9 years. Today, it is 81.9, and by 2045, it is projected to be 88.3.15 The second contributing factor to Japan's aging is that too few young people are replacing old ones as they die. Japan's total fertility rate (TFR) has fallen from 2.75 in 1950 to 1.33 today.16 This is well below the replacement TFR of 2.1.

The math is unforgiving: As people live longer in an environment of fewer and fewer children, median national age increases.17 In 1950, the median age of Japan was 22.3; today, it is 42.9; in 2045, it is estimated to be 52.3.18 By 2025, when Japan could have a median age of 50, 11% of her citizens will be over 80. She will then have as many seniors over 80 as children under 15. For every "retired" person over 65, Japan will have only two working people between 15 and 65.19

Who will man Japan's steel mills and automobile factories and chip assembly lines? Who will pay the pensions of Japan's retirees? Like America and Europe, Japan has built a system of vast entitlement programs. Because, for political reasons, they have become highly underfunded over the years, these programs operate today on a "pay-as-you-go" basis. This means that young workers pay retirees' pensions. However, in a society with fewer young workers and more retired people, who will write these monthly checks?

It is not at all evident that any nation that is aging so fast and so dramatically as Japan is can sustain economic viability, much less growth. Japan's problems may be very long-term indeed.

Japan's is not an isolated case. Graying is "sweeping the Asian/Eurasian region. . . . Only a catastrophe of biblical proportions could forestall the tendency for Asia's population to age substantially between now and 2025."20 Some of these nations will age "at a pace or to an extreme never before witnessed in any ordinary human society."21 "Throughout East Asia, many populations will be more elderly than any yet known, and some will be aging at velocities not yet recorded in national populations."22

Indeed, China's future looks even bleaker than Japan's. China's over-80 population will increase from today's 14.77 million (1.1% of the population) to 100.55 million (7.2% of the population) in 2045.23 This almost seven-fold increase in 45 years translates into real problems for China, because she, unlike Japan, has no national pension system. In a nutshell, "Japan became rich before it became old; China will do things the other way around."24 Chinese seniors will need to depend on younger family members for support. Yet, with so few young people around after 2025 or so (in no small measure the result of her decades-old one-child-per-family rule), there will eventually be almost a one-to-one ratio between elderly retirees and workers. The economic difficulties this math puts on workers will be intense. China's is not a pretty situation at all.

The picture is much the same for North America and Europe. By 2050, fully 20% of Americans will be over 6525, and 42% of Italians will be over 60. By then, Europe will have 75 pensioners for every 100 workers.26 Mexico's aging is truly phenomenal. In 1950, only 0.5% of her population, or 130,000 individuals, was over 80. Today, a full 1% of her population is over 80, a figure that translates to 1.1 million people. By 2045, 5.8% of her population will be over 80, or 5 million people.27 By that time, she will have just crossed the line from absolute population increase to absolute decrease.

Around the World in Eighty Years

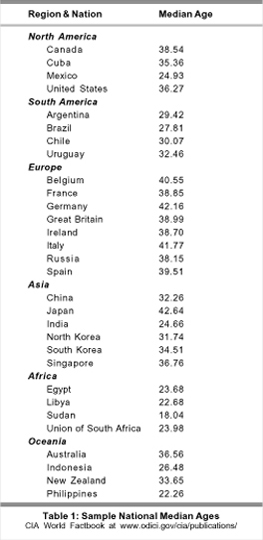

The median age of the world as a whole is 27.60. Table 1: Sample National Median Ages indicates median ages for major nations by region. It is obvious that median age increases with the level of a nation's industrialization.

Globally, the number of individuals over 80 has increased from 13.78 million in 1950, when these individuals represented only 0.5% of the population, to 86.65 million in 2005. Today, the 80-plus cohort represents about 1.3% of the population—a five-fold increase in 55 years. The number of individuals over 80 could increase to 394.22 million in 2045, when they will represent a whopping 4.5% of the world's population.28 By then, the median age of the world will have increased from its 1950 level of 23.9 to 37.8.29

These figures tally more or less with Japan's trend lines. These lines converge to point directly to a world of increasingly stagnant economies, a prolonged period of standard-of-living decline, as nations struggle with ways to support their dependent seniors and maintain industrial and food production with fewer and fewer young workers.

The answer to the economic problems triggered by sub-replacement fertility rates has as its foundation Herbert Hoover's assertion that children represent a folk's "most valuable natural resource." Children are valuable. Politicians, economists, and technologists, all refusing to build on this foundation, offer solutions that address symptoms, not causes. The third installment of this four-part series will focus on some of those solutions and how they miss the mark.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Department of Agriculture figures cited by Richard John Neuhaus, "Where Have All the Children Gone?" First Things, May 2005, p. 58.

2 When combined with industrialization, urbanization has historically resulted in decreased fertility. However, urbanization in pre-industrial economies, as in the Middle East and some Asian nations, has not typically resulted in lower fertility. So it is that sprawling urban centers like Calcutta, Cairo, and Manila are characterized by high fertility rates. Children are everywhere. Statistics clearly show that, as these urban areas industrialize due to globalization, fertility rates decline.

3 Witte, John, Jr., "The Meanings of Marriage," First Things, October 2002, pp. 30-41.

4 Himmelfarb, Gertrude, quoted by Brian C. Anderson, "Capitalism and the Suicide of Culture," First Things, February 2000, pp. 23-30. Along these lines, Stanley Kurtz comments:

Especially in Europe, marriage is morphing into parental cohabitation. And in societies where parents commonly cohabit, the practice of "living alone together" is emerging. There unmarried parents remain "together" yet live in separate households, only one of them with a child.

5 Kurtz, Stanley, "Demographics and the Culture War," Policy Review, February/March 2005. p. 33.

6 Wattenberg, Ben, cited by Kurtz, ibid., p. 36.

7 In "Overcoming Motherhood" (Policy Review, December 2002/January 2003, p.31), Christine Stolba comments that middle-aged women who have deferred childbirth for years "form a large portion of the fertility industry's customers, spending tens of thousands of dollars for a single chance to cheat time." Many have waited too long. "By the time a woman is in her forties, the odds of having a child, even with some form of intervention, are less than 10 percent."

8 Neuhaus, ibid., p. 58

9 Kurtz, ibid., p. 36.

10 Neuhaus, ibid., p. 58.

11 Kurtz. ibid., p. 37.

12 For details, see England, Robert Stowe, Global Aging and Financial Markets: Hard Landings Ahead, Center for International and Strategic Studies, 2002.

13 England, The Macroeconomic Impact of Global Aging: A New Era of Economic Frailty?, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2002. Nicholas Eberstadt ("Power and Population in Asia," Policy Review, February/March 2004) also cites Paul S. Hewitt, "The Grey Roots of Japan's Crisis," The Demographic Dilemma: Japan's Aging Society, Smithsonian Institution, Woodrow Wilson Center, Asia Special Report 107, January 2003, pp. 4-9.

14 See, for example, Herbert London's "Red Sun Rising," The National Interest, Winter 2004/05, p 105. A more useful analysis is that of Peter Hartcher, "Can Japan Come Back?" The National Interest, Winter 1998/99, p.32.

15 World Population Prospects: The 2002 Revision. United Nations Population Division Database, accessed May 20, 2005, available at http://esa.un.org/unpp.

16 World Population Prospects, ibid.

17 Currently, the median age ranges from a low of about 15 years in Uganda and Gaza Strip to 40 or more in several European countries and Japan.

18 World Population Prospect, ibid.

19 Eberstadt, ibid., p. 3.

20 Ibid., p. 11.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., p. 12. The author cites the United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2002 Revision. Also cited is the United States Bureau of the Census, International Database, available at http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idbacc.html.

23 World Population Prospects, ibid.

24 Eberstadt, ibid., p.15.

25 U. S. Census Bureau figures forecast that the age 85-plus segment of the population will grow from 4,259,000 in year 2000 to 13,552,000 in year 2040. All America at that time will be as old as today's "oldest" state, Florida.

26 Kurtz. ibid.

27 World Population Prospect, ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.